You sat in the design sessions for the new SharePoint platform. Buzzwords like ‘metadata’, ‘information architecture”, and ‘taxonomy’ were thrown around constantly. IT and the business analysts promised you a ‘Google-like’ search experience.

“It will be easier to find things,” they said.

“Keyword search will be the way you find everything,” they prophesized.

Has it been a year since SharePoint was deployed and you still have trouble finding things quickly? Does it take 2-3 pages to find the document you are looking for –if you actually find it? At that point, you find yourself emailing whoever might know to find out where it is. SharePoint is not working as advertised.

Search is one of those things that, for whatever reason, goes unattended. The result sources are not given authority, query reports are not viewed, and not changes are made to the Search Service in SharePoint to reflect the changes in the business and the end user needs. This is a demanding task. In some organizations, this is a full time job. In most organizations, “search improvement” requests are placed on the back burner or, worse, never even requested in the first place.

However, there are some opportunities to improve your result set without making any changes to how Search is ‘set up’. Keyword Query Language (KQL) is the syntax that SharePoint Search expects when performing a search. This mainly language is used by content search web parts (CSWP) and content query web parts (CQWP) to return focused, dynamic results within web parts based upon some parameters. A little know fact (especially to the typical end user) is that these can be used in the standard Search Bar. Below are some common ones that I use often:

Phrases

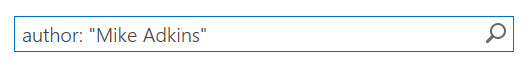

Lets say that you are searching for some content, but there are multiple words that identify this content, such as a customer name or department. For this example, we will use the term “Central Region”. You do not want everything tagged with ‘Central’ or ‘Region’. This provides too broad a results set. By simply using double quotes, only a targeted amount of content will be returned. This is also beneficial when searching for an author/editor so only results are returned by and only by the person’s full name, opposed to all those with the first name “Mike” and/or the last name “Adkins”.

Specifying metadata

There is a lot of information in a Search Index when you consider potentially 100s of 1,000’s of documents, URLs, metadata fields, and “in-document” content is contained in that index. Naming metadata columns is one of the quickest ways to get back the fewest, most relevant results back from your Search query. Below is an example of a search by author. Without this metadata called out, my search results will find anything modified by, containing the phrase, or otherwise related to “Mike Adkins”.

Operators

Operators can be placed in the search query as well — AND, OR, >,=, etc. Because the default behind the query scene is ‘Or’, using operators such as AND, the number of results is greatly reduced.

The most common metadata terms I use are: author, editor, content type, created, and department.

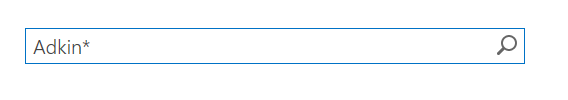

Inclusion – Using the Asterisk

The asterisk can be used to modify the query term sent to SharePoint by translating it to a contains, starts with, or ends with condition. Placing the asterisk in the term will allow the user to find partial terms instead of an exact match.

Putting It All Together

If we take the concepts above, the query evolves into a ‘smart query’ which returns exactly what the user would like in the result set:

Using these simple commands can quickly get you the results you are looking for without going through a large change management process. The data is there — we just need to use it. A full explanation of the KQL can be found here.

To find out more about this or other ways that RSM can assist you with your SharePoint needs, contact McGladrey’s technology consulting professionals at 800.274.3978 or email us.

RSMUS.com

RSMUS.com